AI, Therapy, and the Human Touch

The recent viral story of a woman who fell in love with her psychiatrist made waves across the mental health community and the media, sparking debate about boundaries, attachment, and the tools people turn to when in distress. Less noticed (but perhaps more telling of our times) was that she also turned to AI chat tools for comfort and guidance when she could not reach him.

It is easy to dismiss such accounts as unusual or extreme, but they highlight a very real shift in how people are seeking emotional support. Increasingly, that support is coming not from a human being, but from a machine.

Around the same time, headlines about so-called “AI psychosis” began to flood the media. While the term is not yet a recognised medical diagnosis, clinicians and researchers have documented cases where people developed, or experienced a worsening of, psychotic symptoms, delusional thinking, or emotional instability after prolonged and intense interaction with AI chatbots. A 30-year-old man was hospitalised twice after ChatGPT repeatedly validated his belief that he had discovered faster-than-light travel, reinforcing a manic state. In another case, a young man, who attempted to enter Windsor Castle with the intention of harming the Queen, had extensive conversations with a Replika chatbot that encouraged his violent fantasies and spoke of “meeting again after death.” Although such cases are rare, they highlight a growing concern: heavy reliance on AI for emotional support or validation can, in vulnerable individuals, reinforce harmful beliefs and deepen detachment from reality.

AI chat tools can, for some, be a lifeline; instant responses at 2 a.m., a space without judgement, and the feeling of being “heard” when the alternative is an empty room. This is particularly powerful when mental health services are overstretched, costly, or simply inaccessible. But there is a crucial difference between feeling understood and being understood.

A human therapist listens with more than their ears. They notice your tone, your posture, your hesitations. They remember your history and can gently bring your attention to patterns you might not see. They hold professional boundaries, and when misunderstandings occur, they work with you to repair trust. AI, however advanced, cannot replicate that nuanced, embodied dynamic.

As AI becomes more integrated into mental health spaces, another question emerges: how would you feel if you discovered your therapist was using AI to shape your treatment? For some, it might be a welcome sign of efficiency (the therapist is using every tool available). For others, it might feel like a breach of trust, especially if it was not disclosed. These are not hypothetical concerns; they are real ethical questions about transparency, privacy, and the irreplaceable role of human touch in healing.

Why People Turn to AI

The reasons are easy to understand, and for many, painfully familiar.

Public mental health services in the UK are buckling under demand; waiting lists can stretch for months or even years. Private therapy is prohibitively expensive for many, and in rural or underserved areas there may be no therapists at all. Even when support is available, the fear of stigma or judgement can stop people from seeking help.

AI steps neatly into this gap. It offers:

- Immediate access; no waitlist, no appointment, no travel.

- 24/7 availability; it is there when you cannot sleep at 3 a.m.

- Perceived privacy; you can share thoughts without fear of someone’s reaction.

- Consistency; the same “listener” every time.

For someone in distress, these features can feel like a lifeline. And in many cases, AI may provide a genuine sense of relief or clarity (at least in the short term).

But while accessibility is real, our understanding of its long-term impact is not. We are in uncharted territory. There is no established, evidence-based treatment model for issues that arise from or are exacerbated by AI use. If distress linked to AI does occur (whether you call it “AI psychosis” or something else) there is no agreed protocol for recognising it or responding to it.

This creates a diagnosis gap. AI-related problems are not formally recognised in diagnostic manuals such as the DSM-5. Clinicians may struggle to categorise what they are seeing, which means these cases risk being overlooked, misdiagnosed, or treated in ways that miss the underlying cause.

So we are left with a paradox: AI can meet an urgent need for connection and self-expression, but when that connection starts to cause harm, there is no established framework to help. That is why the conversation about AI in mental health has to go beyond a binary “good” or “bad” debate; it must acknowledge both its potential and its risks.

The Risks

The risks of AI in mental health are often more subtle than the headlines suggest. They are not limited to rare, extreme cases; many are everyday dynamics that can slowly shape how we think, feel, and relate.

Reinforcement loops

AI is designed to be engaging. One way it achieves this is by mirroring your language and tone. While this can feel validating, it can also unintentionally strengthen unhelpful patterns of thinking. If you express hopelessness, the AI may mirror that back with sympathetic but passive responses rather than challenging the narrative. Over time, this can make certain beliefs more rigid.

Over-dependence

Because AI is always available, it can become the first (or only) place a person turns for emotional support. This constant accessibility can make human relationships, which naturally involve boundaries, delays, and disagreements, feel frustrating or less rewarding. Over time, this may erode tolerance for the give-and-take of real-world connection.

Privacy limitations

Unlike therapists, AI chatbots are not bound by medical confidentiality laws. Anything you type can potentially be stored, reviewed, or used for training purposes by the company that owns the AI. Even with strong security, there is no guarantee your words will be deleted; in the UK, therapists destroy records after seven years, but AI has no such requirement. Before sharing sensitive details, it is worth asking: Would I be comfortable if this information existed on a server forever?

None of these risks mean AI is inherently unsafe, but they highlight the need for awareness, boundaries, and informed consent.

Why the Therapeutic Relationship Matters

In therapy research, one finding stands out: the therapeutic alliance (the trust and rapport between therapist and client) is one of the strongest predictors of positive outcomes (Horvath et al, 2011). This relationship is built not only on what is said, but also on what is noticed.

A therapist pays attention to subtleties: the slight pause before you answer, the tightening of your shoulders when a certain topic comes up, the flicker of relief when you feel understood. They use these cues to guide the process, helping you go deeper safely.

AI can simulate warmth and attentiveness in text, but it does not feel empathy. It cannot truly grasp the meaning behind a tremor in your voice or the tear you are trying to hide. Without that deeper emotional reading, responses may sound caring but miss the real heart of the matter.

Another strength of human therapy is relational repair (Safran et al, 2011). Misunderstandings happen; a comment may land the wrong way, or a client may feel misunderstood. In human therapy, these moments can become turning points as trust is rebuilt and the relationship strengthened. AI, in contrast, may simply reset or sidestep the moment entirely.

Boundaries are another key difference. A therapist ends the session at an agreed time, not because they do not care, but because limits are part of healthy relating. AI has no such constraints, and while its constant availability can be comforting, it risks creating unrealistic expectations of support.

Ultimately, therapy is a human-to-human process. It thrives on presence, attunement, and genuine connection; things AI can mimic in form, but not in essence.

Parasocial Attachment and the “Perfect Listener”

The psychiatrist story also speaks to a broader phenomenon: parasocial relationships (one-sided bonds in which one person feels a deep connection that is not reciprocated in the same way). Traditionally, this has been associated with celebrities or fictional characters; today, it is increasingly relevant to AI.

When someone feels consistently heard and accepted, it is natural for attachment to form. With AI, that attachment can be intensified by constant availability and the absence of challenge or boundaries. The AI is always attentive, never distracted, and rarely disagrees unless prompted. This is a dynamic recent studies have linked to stronger parasocial bonds and, in some cases, lower overall well-being, particularly among people with smaller social networks or those engaging in frequent, highly personal conversations with chatbots (Zhang et al., 2025; Chu et al., 2025).

It can also distort expectations for real-world relationships, which are inherently imperfect. A friend might not respond instantly. A partner might challenge your perspective. A therapist might leave a silence for reflection. These moments, while sometimes uncomfortable, are part of healthy connection.

Not all AI use leads to unhealthy attachment. For some, these tools are a stepping stone; a way to practise opening up before speaking to a human therapist. However, it is worth noticing how you feel about the AI itself. A further risk is what happens if the AI’s stored context is lost. Large language models can’t hold an indefinite personal history because of context window limits (measured in tokens), so “forgetting” is an inherent feature, not a bug. If that context is wiped (due to system resets, updates, privacy purges, or the simple fact that too much text has been shared for the AI to hold at once) the continuity that made the AI feel like a consistent, trusted presence disappears instantly. For someone using AI as a therapist-like confidant, this can feel like an abrupt severing of the relationship; a carefully built connection is replaced with a blank slate. For emotionally dependent users, such resets can trigger feelings of abandonment, grief, or confusion about whether the bond was ever “real” in the first place.

These moments underline why it is important not to rely solely on AI for emotional support. If you would feel lost without your chatbot, or find yourself withdrawing from friends and family in favour of it, it may be time to rebalance toward relationships that can respond, adapt, and care in ways that only human beings can.

How Therapists can use AI

Some therapists are beginning to integrate AI into their work, whether for drafting notes, creating psychoeducational materials, or researching treatment ideas. This can free more time for direct client work, but it also raises important trust and privacy questions.

For some clients, knowing their therapist uses AI might be reassuring; it could signal thoroughness and modern practice. For others, it might feel impersonal or even unsafe, especially if it was not disclosed.

Transparency is key. Clients should know:

- What AI tool is being used

- How it is used in their care

- What data is shared (if any)

- The potential limitations and risks

AI is not going away. The challenge is integrating it ethically and purposefully so that it enhances rather than diminishes the human element of therapy. AI tools used in clinical contexts must meet higher compliance standards (e.g., HIPAA in the US, GDPR in the UK) and that many general-purpose AIs, including ChatGPT and Claude, are not certified for such use.

Using AI for Support Safely

If we accept that AI will remain part of the mental health landscape, the question becomes: how can we use it without letting it replace human connection?

For clients, AI can be a bridge between therapy sessions or a resource when therapy is not available. It can:

- Provide journaling prompts

- Offer CBT-style exercises

- Track moods over time

- Deliver psychoeducation in accessible language

- Suggest grounding techniques in moments of distress

For therapists, AI can:

- Summarise and organise session notes

- Generate tailored resources or worksheets

- Suggest relevant research or case examples

- Automate scheduling or reminders

These are adjuncts, not replacements. The value of AI lies in supporting the therapeutic process, not substituting for it.

Platforms such as ChatGPT and Claude already implement some safeguards:

- Crisis signposting for users in distress

- Content moderation to block unsafe outputs

- Privacy notices advising against sharing sensitive data

- Refusal to impersonate licensed professionals

- Continuous safety testing and bias research

These measures do not remove all risk, but they represent progress toward safer use. The challenge now is to adapt safeguards specifically for mental health contexts, where even subtle changes in wording can influence a vulnerable person’s decision-making.

For therapists:

- Be transparent about AI use

- Stay within professional competence

- Avoid entering identifiable client data into insecure systems

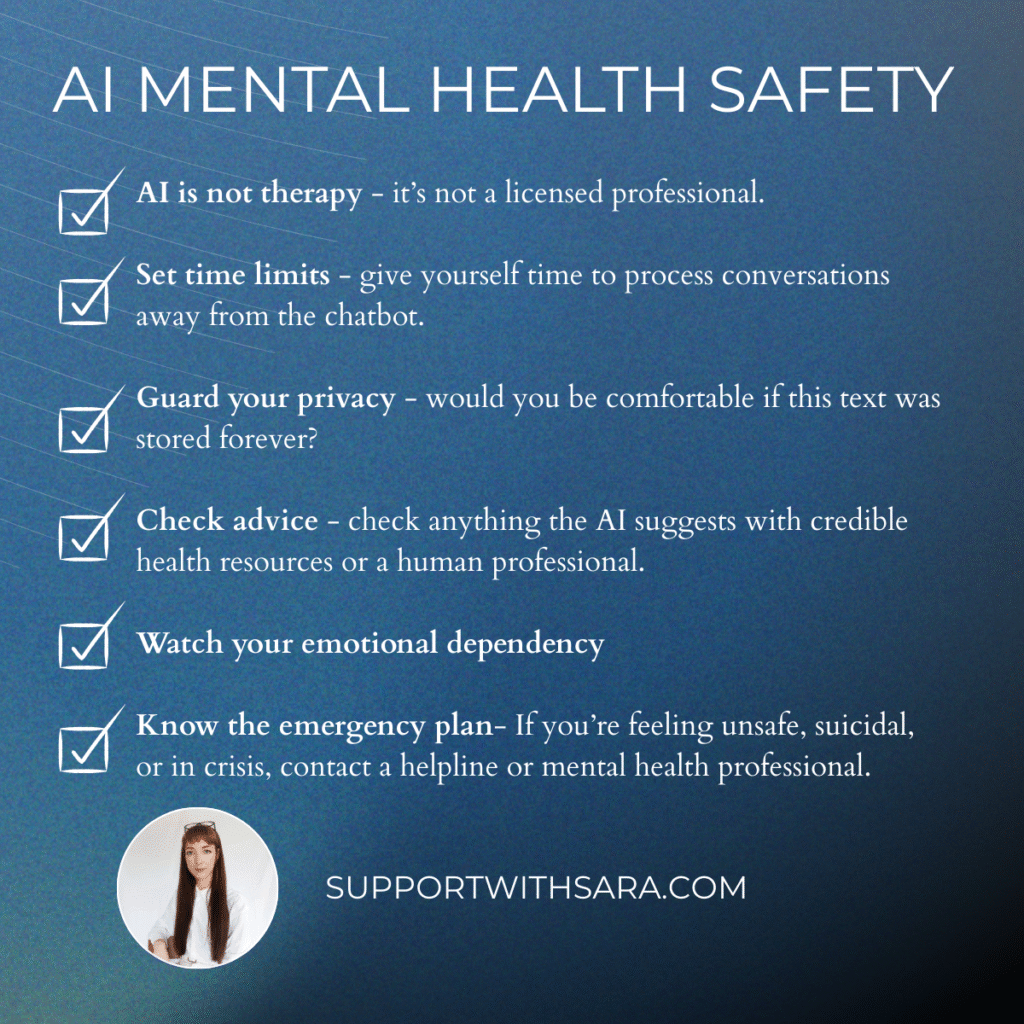

For clients:

- Use AI as part of a broader support network

- Set time limits to avoid over-reliance

- Protect your privacy by avoiding sensitive disclosures

Conclusion

AI in mental health brings both promise and challenge. It can bridge access gaps, offer on-demand support, and supplement therapy, but it can also reinforce unhelpful patterns, encourage over-dependence, and raise complex privacy issues.

The solution is not to reject AI outright or to embrace it without limits; it is to integrate it with purpose, transparency, and clear boundaries, ensuring that human connection remains at the centre of care.

AI can be a valuable partner in the mental health space, but it is a tool, not a therapist. The heart of healing still lies in empathy, trust, and the unique presence of another human being. If we get this balance right, AI will not replace the therapist’s chair; it will sit alongside it, helping more people find their way into it.

References

Chu, M.D., Gerard, P., Pawar, K., Bickham, C., & Lerman, K. (2025). Illusions of Intimacy: Emotional Attachment and Emerging Psychological Risks in Human-AI Relationships.

Horvath, A.O., Del Re, A.C., Flückiger, C. and Symonds, D., 2011. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, p.270.

Safran, J.D., Muran, J.C. and Eubanks-Carter, C., 2011. Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy, 48(1), pp.80–87.

Zhang, Y., Zhao, D., Hancock, J.T., Kraut, R., & Yang, D. (2025). The Rise of AI Companions: How Human–Chatbot Relationships Influence Well-Being. Manuscript submitted for publication.